At the beginning of the 20th century, Ireland found itself at the epicenter of events that eventually led to its long-awaited independence from British rule. One key moment was the Easter Rising in April 1916, initiated by Irish republicans. They rebelled against British rule and declared the Irish Republic, but the uprising was quashed, and its leaders were executed.

Irish America waited on tenterhooks for news from Ireland and the 1916 Easter Rising so much so that in the midst of World War One it was front-page news on the New York Times for two weeks.

The Leaders of the Easter Rising in Ireland (1916)

Leaders of the Easter Rising in Ireland in 1916 were representatives of Irish republicans who organized and participated in the events. The most prominent figures in this uprising were:

Patrick Pearse

He was one of the main organizers of the rebellion and declared the Irish Republic outside the General Post Office in Dublin. Pearse was one of the seven leaders executed after the suppression of the uprising.

James Connolly

He led the Irish Socialist Republican Army (ISRA) and was one of the chief organizers of the uprising. Connolly was severely wounded in battle and was executed while tied to a chair due to his health.

Thomas Clarke

An experienced revolutionary and one of the oldest participants in the uprising. He was also executed after the failure of the rebellion.

Joseph Plunkett

Second in command to Pearse in organizing the uprising. Plunkett was suffering from tuberculosis and married Grace Gifford shortly before his execution.

Thomas MacDonagh

He was also a key participant in the uprising and was executed on the same day as the other leaders.

These leaders of the Easter Rising are considered martyrs in the struggle for Irish independence, and their sacrifices played a significant role in shaping public opinion in Ireland in favor of independence. Following the uprising, Ireland gradually moved towards full independence, culminating in the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Origins of Rebellion: The Road to Irish Republic

The root causes of the rebellion lie in a complex socio-political context. A religious conflict between Protestant Anglicans and Catholic Irish led to inequality and heightened societal tensions. Prolonged oppression of Irish landowners, coupled with economic difficulties exacerbated by famine, intensified public dissatisfaction.

Hostility between Catholics and Protestants persisted, exacerbated by Britain’s use of the island as a colony for exploitation. Over time, the Irish nationalist movement grew, and after decades of brutal conflicts, Britain divided the country in 1921. Ireland, with a Catholic majority, gained independence, while Northern Ireland, described as a “Protestant state for a Protestant people,” remained part of the United Kingdom.

However, not all residents of Northern Ireland wanted to be associated with Britain, and the newly formed nation was embroiled in religious violence from the outset. Catholics, governed by Protestant officials who discriminated against them and unevenly enforced laws, insisted on equal treatment and political independence.

In 1918, the British Parliament passed a conscription law for the Irish, further fueling resentment among the Irish population. In response, Irish deputies withdrew from the British Parliament and established their own national parliament, known as Dáil Éireann. This act marked the first step toward the creation of a new state—the Irish Republic, which declared its independence.

Dáil Éireann is the lower house of the Oireachtas, which is the Irish Parliament. The establishment of Dáil Éireann is historically significant in the context of Ireland’s struggle for independence from British rule.

The first Dáil Éireann was convened on January 21, 1919, following the 1918 general election. During this session, members of the Sinn Féin party, who won a majority in the election, declared Irish independence and established the Irish Republic. This event marked a crucial step in the establishment of an independent Irish state.

The declaration of independence and the subsequent establishment of Dáil Éireann were part of a series of events that eventually led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which paved the way for the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922.

Challenges in the relations between Ireland and Britain led to the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922. The new state became independent from Britain, but the division resulted in the creation of two entities: the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The Good Friday Agreement graffiti in Belfast, Northern Ireland

In 1801, Ireland was joined to the United Kingdom as a result of the Act of Union. However, differences in religious and cultural beliefs became a source of tension. By 1919, national ambitions led to a rebellion, and the subsequent Irish War of Independence laid the groundwork for future division.

The Irish National Assembly, proclaimed in 1919, became a forum for expressing aspirations for independence. Tensions between Britain and Ireland reached a climax during the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), where the Irish fought for their autonomy.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 formalized Ireland’s partial independence, creating the Northern Ireland Parliament. However, this compromise did not satisfy everyone, and Ireland became a republic in 1949, completely renouncing British influence.

The political landscape continued to evolve, marked by struggles for civil rights and nationalist aspirations. The late 20th century witnessed efforts to address these issues through peace negotiations. The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 played a pivotal role in promoting reconciliation and stability in the region.

Despite progress, historical and cultural differences persist, shaping the complex dynamics between Ireland and the United Kingdom. The legacy of the Irish War of Independence and subsequent events continues to influence the socio-political landscape of both nations.

Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921

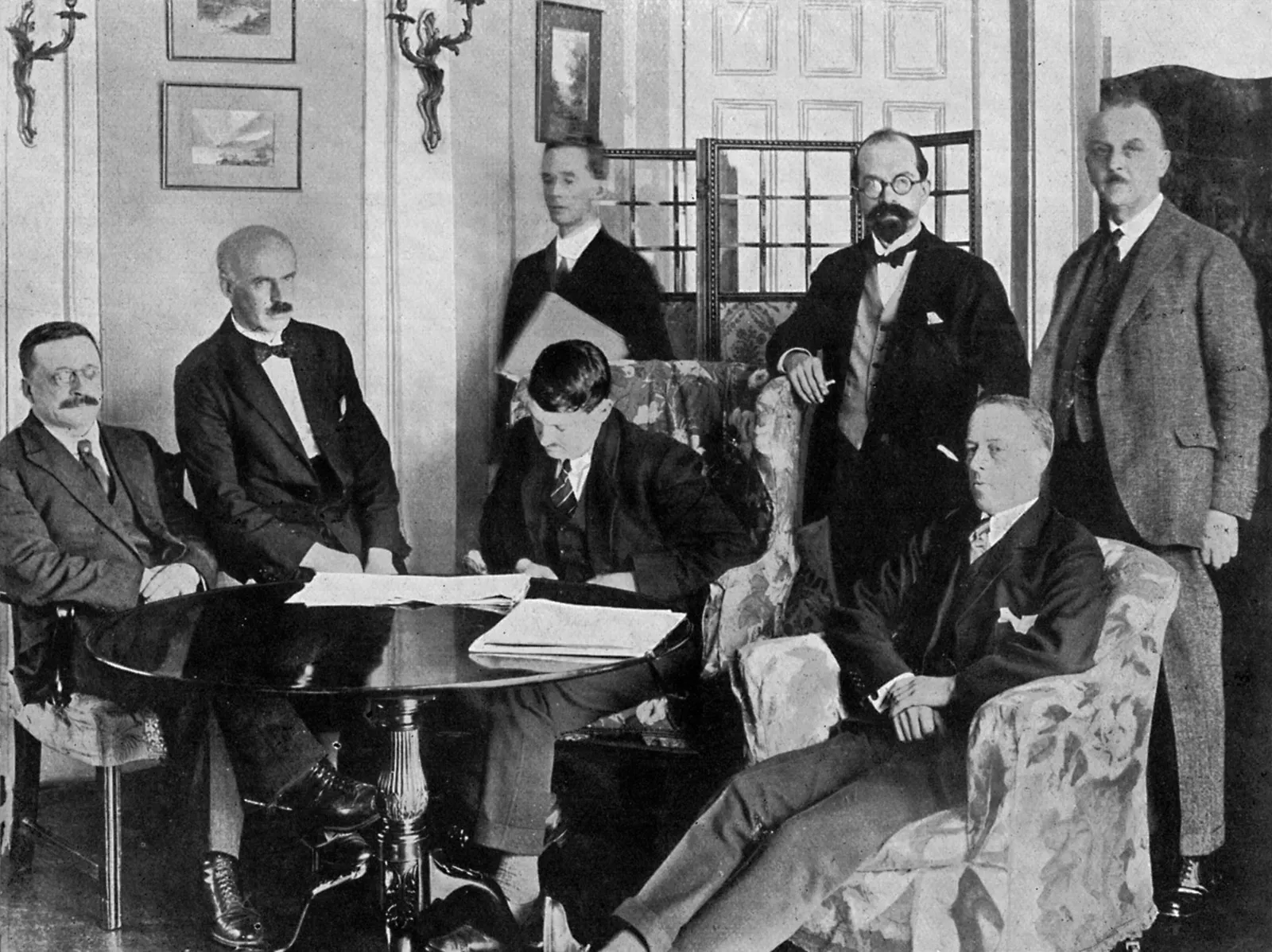

Members of the Irish delegation while signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, also known as the Anglo-Irish Agreement, was signed between representatives of Great Britain and Ireland, playing a crucial role in determining Ireland’s future relationship with the British Empire. Here are the key provisions of this treaty:

Independence and Anglo-Irish Union: The treaty granted Ireland the status of the Irish Free State, signifying formal partial independence from Great Britain. It became a dominion within the British Empire with the right to its own constitution and government.

Northern Ireland: The treaty provided for the establishment of the Northern Ireland Parliament, which could choose to opt out of the newly formed Irish Free State within one month of the treaty coming into effect. This led to the division of Ireland into two parts: the republic and Northern Ireland, which remained part of the United Kingdom.

- Oath of Allegiance: Members of the new government of the Irish Free State were required to take an oath of allegiance to the British monarch.

- Defensive Alliance: The treaty provided for a defensive alliance between Great Britain and Ireland, as well as the possibility of establishing a joint military council to coordinate defense matters.

- Minority Rights: Measures were introduced to protect the rights of the Protestant population in Northern Ireland, where Protestants constituted the majority, within the new political context.

Despite the signing of the treaty, it remained a subject of intense political and national debate. Disagreements over the status of Northern Ireland and obligations to the British Crown led to the Irish Civil War and, subsequently, a change in the status of the Irish Free State.

The establishment of two Irelands occurred after the enactment of the Government of Ireland Act in 1920, which established Northern and Southern Ireland as dominions within the British Commonwealth. The Republic of Ireland became an independent state, while Northern Ireland remained part of the British Commonwealth.

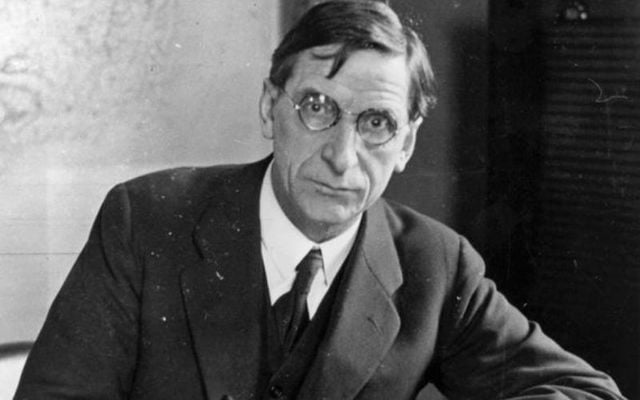

We are not just seeking freedom from external domination but also aspire to the creation of a fairer and more egalitarian society within our country.

Éamon de Valera (President of the Irish Republic)

Éamon de Valera (President of the Irish Republic)

The sacrifices of the leaders of the Easter Rising became a symbol of the national struggle, leading to the establishment of Dáil Éireann and the ultimate assertion of Ireland’s state sovereignty. Despite subsequent challenges and the division into Northern and Republic of Ireland, the national aspiration for freedom and justice remains an integral part of Irish history, shaping intricate dynamics in the relations between Ireland and Britain to this day.

Political, Religious, and Ethnic Dynamics in the Aftermath of Conflict

The Ulster Conflict, also known as “The Troubles,” remains one of the most complex and significant events in the history of Northern Ireland. From the late 1960s until the signing of the Belfast Agreement in 1998, this conflict served as a battleground for political, religious, and ethnic clashes, resulting in tragedies and destruction. In this article, we will delve into the roots of the conflict, its escalation, and the path to peace proposed by the Belfast Agreement.

Political Disputes

Political differences between Catholics and Protestants became a source of tension, defining the status of Northern Ireland and sparking intense political debates.

Religious and Ethnic Tensions

Religious and ethnic disparities between Catholics and Protestants led to conflict, where identity played a pivotal role in shaping political affiliations.

Civil Rights and the Equality Movement

The conflict began in the context of the civil rights movement but quickly transformed into open confrontations and terrorist acts carried out by various groups.

Escalation of Violence

In the 1970s, the conflict turned violent, with groups like the IRA and Unionist paramilitaries actively employing violence to achieve their goals.

Path to Peace

The signing of the Belfast Agreement in 1998 marked a turning point, providing the general population of the region the opportunity to determine their future through self-governing institutions.

Process of Peaceful Reconciliation

The process of peaceful reconciliation included the integration of institutions and the removal of barriers between different groups, laying the foundation for recovery and societal cohesion.

Consequences and Lessons

The conflict left profound consequences in the form of loss of life and destruction. Lessons from this period underscore the importance of dialogue, respect for diversity, and a commitment to compromise in post-conflict societies.

The Ulster Conflict has become part of Northern Ireland’s history, leaving deep wounds but also serving as an example of how peace and reconciliation can be achieved even after a prolonged period of tension and hostility. The opportunity for recovery and development now lies in the hands of a society willing to embrace the lessons of the past to build a more sustainable and harmonious future.

Losses, both physical and emotional, remain in the memory of individuals and society. In addition to physical destruction, many families and communities have experienced tragic losses. It is crucial to understand that these losses leave long-lasting imprints and impact collective consciousness.

The present still reflects echoes of the past in the form of certain sociocultural and political dynamics. For instance, in the political landscape of Northern Ireland, issues related to identity, religious differences, and questions about the region’s status persist. While most people aspire to peace and reconciliation, challenges endure, emphasizing the importance of continuing in-depth dialogue to seek sustainable solutions.