This is often explained with a single word: neutrality. But neutrality was never the cause. It was the outcome. Switzerland’s survival was the result of a long historical process shaped by military defeat, geographical reality, and a brutally pragmatic understanding of power.

The first decisive moment came in 1515, at the Battle of Marignano. Until then, Swiss cantons were active military players in Europe. Swiss infantry was feared, disciplined, and in high demand as mercenaries. The defeat by the French forces of Francis I was not merely tactical; it was existential. It revealed the limits of expansion for a small, mountainous country surrounded by emerging great powers. One year later, in 1516, Switzerland signed the “Perpetual Peace” with France. This was not pacifism. It was strategic retreat.

More than three centuries later, this logic was formalised internationally. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, European powers officially recognised Switzerland’s permanent neutrality. By that point, neutrality was already deeply embedded in Swiss political culture. The country had learned that survival depended not on conquest, but on making itself an unattractive target.

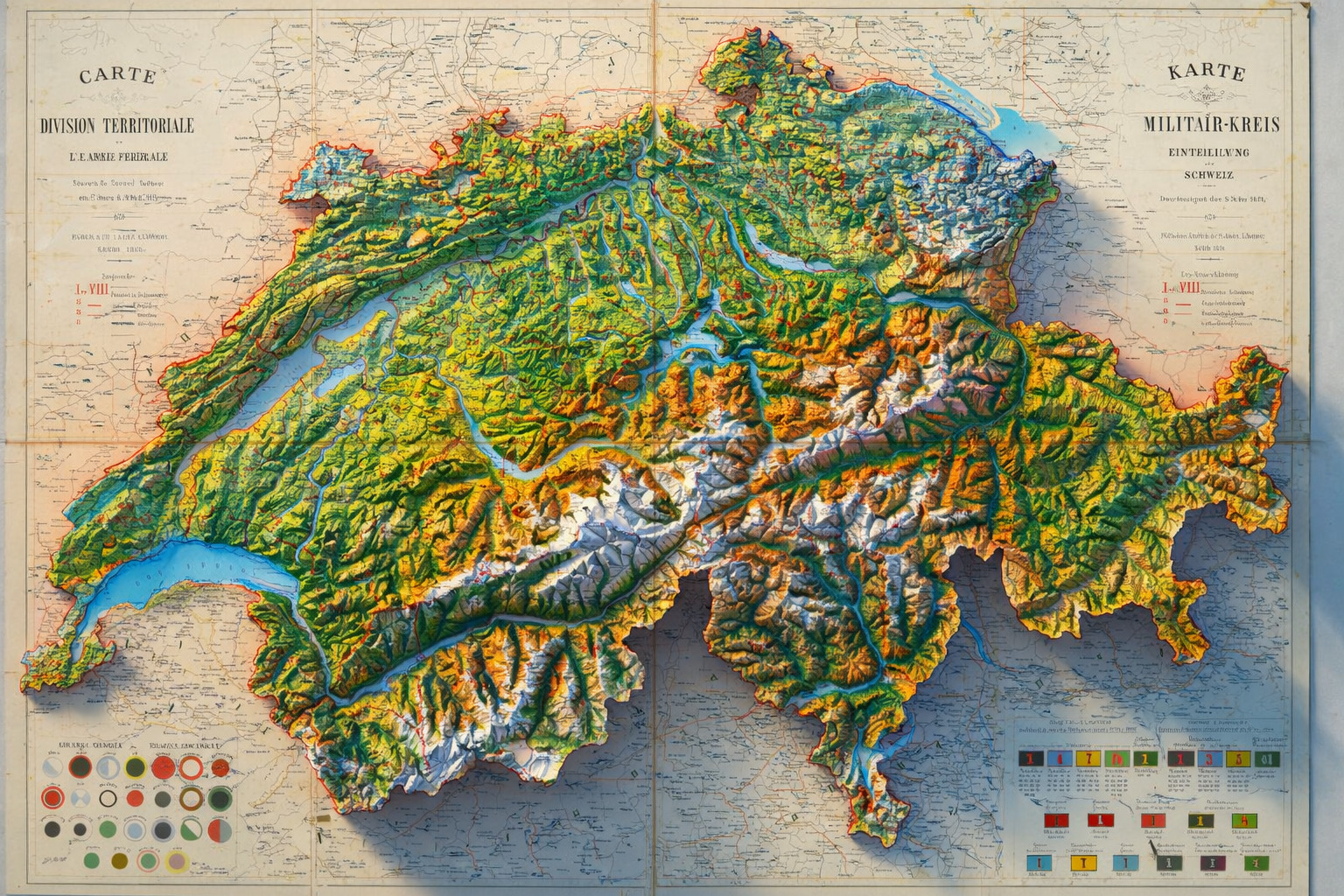

Geography made this possible. A glance at the map explains much. Over sixty percent of Switzerland is covered by the Alps. Movement through the country is constrained by a limited number of passes such as Saint Gotthard, Simplon, and Lötschberg. These routes are natural choke points. Control them, and the country is sealed. Lose them, and any invading army is trapped in hostile terrain.

Unlike Belgium or Poland, Switzerland is not a corridor. It does not offer a fast route to imperial capitals. It provides no strategic shortcut. Any invasion would be slow, expensive, and logistically fragile. Mountains strip attacking forces of speed, supply efficiency, and numerical advantage. Geography alone does not guarantee safety, but it buys time — and time is everything in war.

Switzerland did not rely on geography alone. It transformed terrain into doctrine. By the late nineteenth century and fully developed in the 1930s and 1940s, the country adopted what became known as the National Redoubt strategy. The idea was radical. In the event of invasion, Swiss forces would not defend the borders. They would withdraw deliberately into the Alpine heartland, destroying bridges, tunnels, railways, and fuel depots behind them.

The central Alps would become a self-contained fortress. Mountain artillery, hidden bunkers, and stockpiled supplies would allow resistance for months. Occupying forces would inherit a devastated, fragmented territory impossible to control or exploit.

This was not theory. During the Second World War, Nazi Germany developed concrete invasion plans under Operation Tannenbaum between 1940 and 1941. Swiss neutrality did not protect the country by itself. What mattered were the calculations. Switzerland mobilised more than 400,000 soldiers in 1939, out of a population of roughly four million. Its army was trained specifically for mountain warfare. Fortifications were embedded directly into rock faces, camouflaged to resemble natural formations.

Many of these fortifications were so well hidden that even Swiss civilians were unaware of their existence. Foreign intelligence services never possessed a complete map of Swiss defenses. The country was protected not only by mountains, but by uncertainty.

A rarely discussed secret underscores how far Switzerland was prepared to go. For decades, well into the 1990s, critical bridges, tunnels, and mountain roads were constructed with pre-installed explosive chambers. Not plans for demolition — actual embedded charges. In the event of invasion, the country was prepared to destroy its own infrastructure within hours, cutting itself into inaccessible fragments.

Switzerland was willing to make itself unusable.

The psychological dimension of this strategy mattered just as much. In July 1940, after France had fallen and much of Europe was under Nazi control, Swiss political and military elites faced immense pressure. At that moment, General Henri Guisan, commander-in-chief of the Swiss army, summoned senior officers not to a bunker or headquarters, but to the Rütli Meadow — the symbolic birthplace of the Swiss Confederation.

There, in a closed meeting, he made Switzerland’s position unmistakably clear. There would be no capitulation. Retreat meant withdrawal into the Alps. Resistance would continue even if the country stood alone. It was a calculated act of symbolism designed to solidify resolve. After Rütli, doubts vanished. Switzerland’s defense was no longer just a plan; it was a collective commitment.

The contrast with neighboring countries is striking. Belgium, largely flat and strategically exposed, was overrun within weeks in both world wars. Poland, lacking natural defensive barriers and attacked from multiple directions in 1939, had no depth to retreat into. In both cases, geography limited options regardless of political will.

Switzerland chose a different path. It invested in universal military service, rapid mobilisation, and civil defense. For much of the twentieth century, soldiers kept their weapons at home. The message to any potential occupier was clear: there would be no peaceful rear, no secure territory, no moment of control.

After 1945, this logic only intensified. During the Cold War, Switzerland built one of the densest bunker networks in the world. Even today, the country maintains shelter capacity exceeding its population. Defense was not symbolic. It was structural.

This is why Switzerland did not fight wars. Not because it rejected force, but because it mastered deterrence. It made itself expensive to attack, difficult to occupy, and strategically unrewarding. Neutrality was not a moral posture. It was a system.

History often celebrates power through expansion. Switzerland demonstrates a different lesson. Sometimes survival depends not on strength displayed outward, but on the ability to make oneself a terrible place for war.

And in that sense, Switzerland did not escape European history. It understood it better than most.