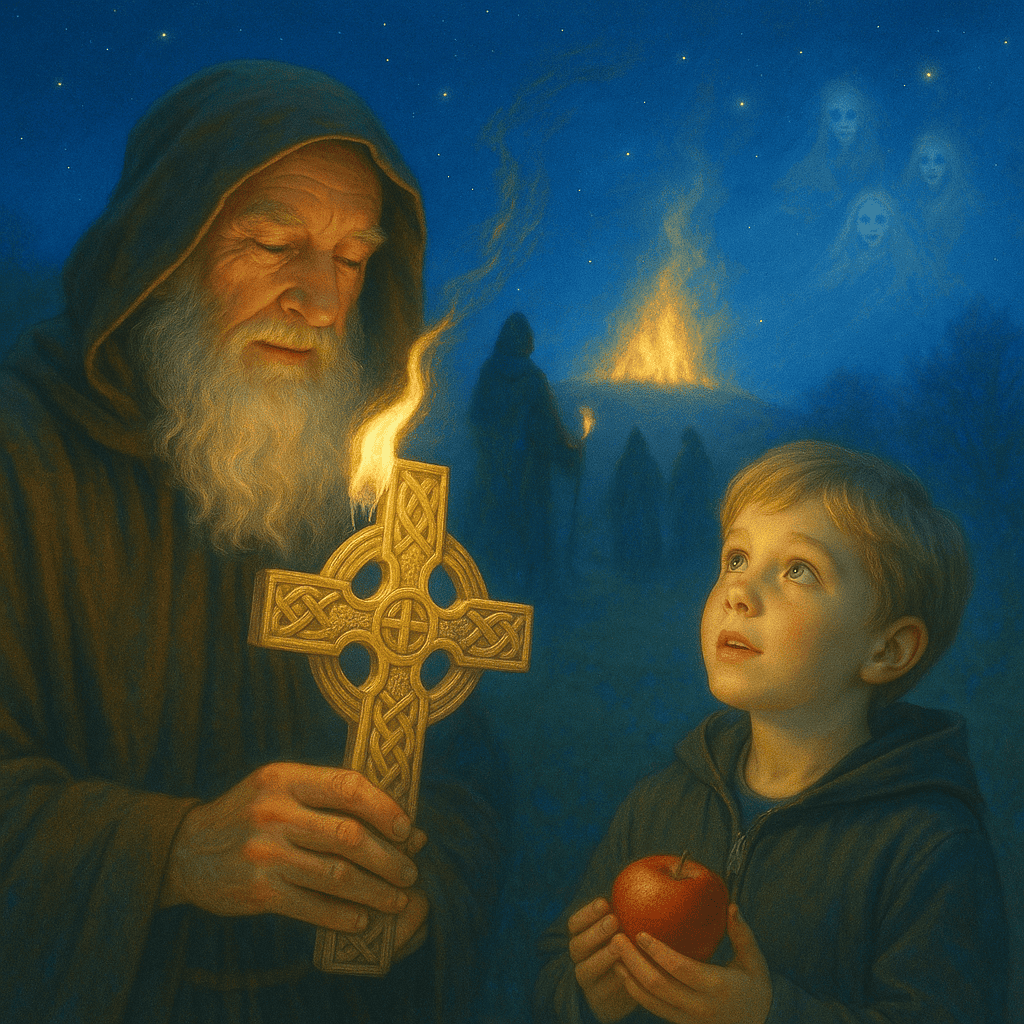

Samhain, pronounced “sow-in,” was the Celtic New Year, celebrated on the night of October 31st and the day of November 1st. It was a night when the old gods still wandered and the living might hear the voices of their ancestors in the wind. The people of Ireland, especially those living near the ancient centers of Tara and Tlachtga, gathered around enormous bonfires lit by druids. From these flames, households took embers to relight their own hearths — a symbol that the warmth of community and faith would endure through the long cold months ahead. Children and elders alike knew that this was no ordinary night. Spirits, both kind and mischievous, were believed to cross freely between worlds. Food and drink were left on doorsteps to welcome them, and to appease the wandering dead or the fair folk known as Aos Sí.

The myths told of great heroes and gods who returned each Samhain. The Tuatha Dé Danann, the divine tribe of the goddess Danu, were said to rise from the mounds — the sidhe — to walk among mortals. In stories, warriors met these otherworldly visitors at the ancient hill of Tara, where the kings of Ireland once held counsel. One of the most famous tales tells of Niall of the Nine Hostages, who met a hideous hag at a sacred well during Samhain. When he kissed her without fear, she transformed into the radiant goddess Ériu, spirit of the land itself, and he was granted the right to rule Ireland. It was a parable that taught the people that truth and beauty often come disguised, and that courage must outlast appearances.

As Christianity took root, Samhain became Lá Samhna, the first day of winter, and later merged with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. Yet beneath the church bells, the old rhythms continued. In every cottage, families lit candles in memory of the dead. They called it Féile na Marbh — the Festival of the Dead. On the coasts, women carried bread and flowers to the sea, whispering prayers for husbands and sons lost to storms. In inland villages, apples were gathered in baskets, and children played games of fortune, trying to catch them from a bowl of water — echoes of long-forgotten divination rituals. Even the mischievous Púca, a shapeshifting spirit who blessed or spoiled the harvest, was honored with offerings of fruit and milk. To ignore the Púca was to invite his tricks into your fields.

To the ancient Irish, November was never a time of despair. It was a time of remembering. The earth rested, but the seeds of the next season were already alive beneath the frost. The nights grew long, but the fire in the hearth burned brighter. It was believed that those who honored their ancestors during Samhain would receive protection for the year to come. The flame on the hearth was the heart of the home — as sacred as the bonfires on the hills — and it was said that the spirits of loved ones might gather around it, unseen but felt, bringing warmth from the other side.

In rural Ireland, Samhain was also practical magic. The changing weather demanded preparation. Livestock was counted and sorted, tools were repaired, and every family made colcannon — mashed potatoes with kale and onions. Into the dish, they sometimes hid a small ring. Whoever found it was said to marry within the year. These simple acts turned survival into ceremony. The people did not separate work from worship; they understood that every gesture, if done with intention, kept the world in balance.

As centuries passed, the myths of Samhain transformed but never died. Halloween, the global echo of this ancient festival, still carries pieces of its soul. The costumes and masks that children wear today are faint memories of the disguises once used to fool wandering spirits. The glowing jack-o’-lantern, carved now from pumpkins, was once a burning coal placed inside a hollowed-out turnip — a lantern for the souls finding their way through the dark. In modern Ireland, bonfires still flare on hillsides, and families tell ghost stories that are really old prayers in disguise.

To understand Samhain is to understand the Irish way of seeing time — not as a straight line but as a circle. Death is not an end but a returning; silence is not absence but a pause before the next song. Even today, in November, the air in the countryside feels thick with memory. In the west, where rain falls softly on stone fences and bog grass, you can feel how near the past still is. The fields that sleep under frost remember every seed that has ever been sown, just as the people remember every soul who has ever walked beside them.

The myths speak quietly now, but they have not gone. The spirits of Samhain remain in the rhythm of Irish life — in the weaving of wool, in the lighting of a candle, in the storytelling by fireside. Mothers tell children about the night when the dead return, not to frighten them but to teach them that love crosses every distance. Students visit ancient mounds and realize they are standing at the hinge of history and eternity. The farmers still watch the moon — the Harvest Moon giving way to the Hunter’s Moon — marking the pulse of the year just as their ancestors did.

So when November arrives in Ireland, it is not simply a change in the calendar. It is a memory blooming again, a quiet reverence in the heart of the dark season. Samhain reminds the Irish that endings and beginnings are only different names for the same doorway. The fires burn to honor what was, and to protect what is yet to come. The wind that sweeps across the hills might be just wind — or it might be the whisper of the old gods, reminding the living that nothing, not even death, can silence what is remembered.