A Day of Contracts and New Seasons

Autumn brought not only colder days but also new obligations. On Michaelmas debts were paid, leases renewed, and servants hired. It was one of the “quarter days” when legal and financial arrangements were settled. In some towns, mayors were elected on this date. For students, it marked the beginning of the university year; for farmers, the end of the fishing season and the start of the hunting season.

St Michael and the Symbol of Light

In art, St Michael is shown with a sword, defeating a dragon. For generations here, he was seen as a heavenly protector against darkness and injustice. As the days grew shorter, the belief in Michael as a guardian of light took on special meaning.

When and Why Traditions Faded

The decline of Michaelmas as a community festival began in the 19th century, as Ireland shifted away from an agricultural way of life and towards industrialisation.

- In rural society, seasonal festivals were essential, tying together harvests, contracts and community life.

- With the growth of towns and industry, these seasonal customs became less relevant.

- Younger generations left villages, religious practices changed, and many folk customs came to be seen as “outdated.”

Some traces survived in the academic and legal calendar — the autumn university and court term is still called Michaelmas term — but the big goose markets, fairs and shared feasts disappeared.

Why Michaelmas Still Matters

Even though most customs have vanished, Michaelmas still resonates for us today.

- Connection with the past. Michaelmas reminds us how closely life once followed the rhythms of nature. In our age of technology, there is a growing interest in heritage and folklore.

- Education and law. Universities and courts still use the name Michaelmas term, keeping a direct link with the old cycle.

- Food and tourism. The “Michaelmas goose,” apple pies, and the last blackberries of the season could all be reimagined as part of Ireland’s culinary and cultural brand.

- Eco-trends and sustainability. Returning to seasonal produce and old calendars fits with today’s slow living and environmental awareness.

- Folklore and legend. Stories of the púca, weather omens and the battle of Michael and the devil make this day a natural part of cultural tourism.

Michaelmas is not only a page from history. It is a key to our identity, one that can inspire education, tourism, food culture and sustainable living.

The Goose Harvest and Folk Beliefs

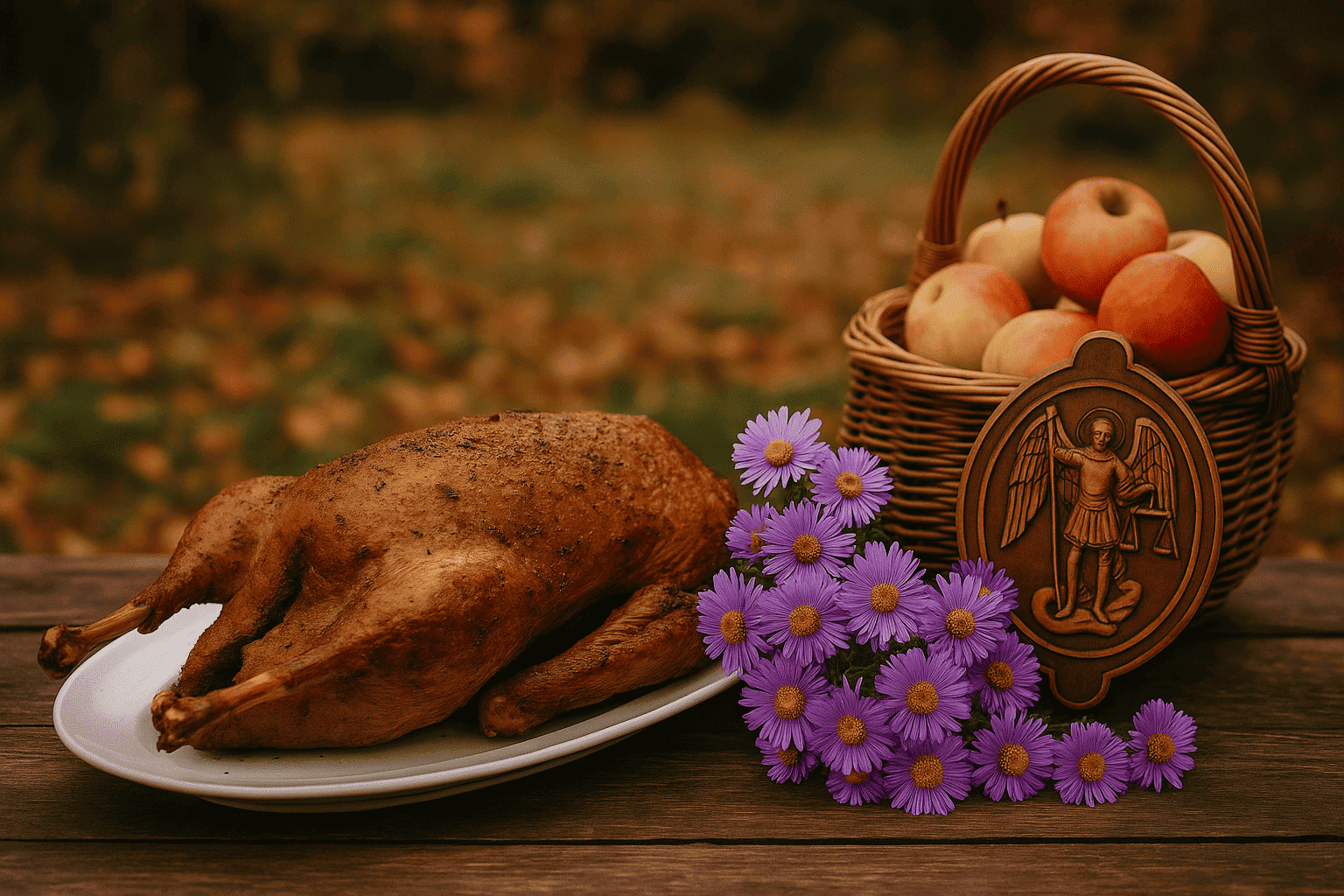

The traditional feast was the Michaelmas goose. Hatched in spring and fattened on the stubble after harvest, geese were at their best by late September. They were roasted, shared with neighbours or given to the poor. In some regions, a sheep was slaughtered instead and the meat divided among families — the so-called “St Michael’s portion.”

A legend tells of a king’s son who choked on a goose bone but was revived by St Patrick. In gratitude, the king ordered that every Michaelmas a goose be sacrificed in honour of the saint.

Michaelmas also marked the last of the harvest. Apple pies were baked, and children were warned not to eat blackberries after this day. According to lore, the devil, cast from heaven, fell on a bramble bush and spoiled the fruit — in Ireland it was said to be the mischievous púca.

Flowers, Fairs and Pilgrimages

September flowers such as asters were called “Michaelmas daisies.” Children made chains of them, and boys born around the feast were often named Michael or Micheál.

Across Ireland there were goose fairs, markets and even processions. In Tramore, Co Waterford, people carried an effigy called Micilín to the sea, symbolising the end of the fishing and tourist season. Pilgrimages were made to holy wells of St Michael, finished with a sip of the well water.

Michaelmas as Personal Memory

For many of us, Michaelmas is not only something found in folklore books but part of family memory. We grew up hearing grandparents warn not to touch blackberries after the end of September. Some households still joked about the “Michaelmas goose,” even when no goose was cooked anymore.

In villages, people used to say Michaelmas was the moment when summer finally gave way. Bonfires, the first school notebooks, the crisp morning air — all of these were tied to St Michael’s Day.

Today, as Ireland seeks balance between past and future, these details feel even more valuable. They remind us that our grandparents lived in tune with nature, and that every generation finds its own way to face the dark season and hold on to the light.